At 4.1 million, post 9/11 veterans number nearly half the size of the Vietnam veteran population. Many of these warriors have been deployed more than once, which creates a distinction between them and many older veterans, who have been deployed only once. They are incredibly diverse in race, gender, and age. Women make up 17.4% of post 9/11 veterans, more than double the number of women veterans overall. They make a unique group, that have very specific needs when they come back into civilian society.

One distinction of consequence is that a little over 41% of all OEF and OIF veterans have a service-connected disability rating, says the Department of Veteran’s Affairs.

This is in comparison to 25% of previous generations. There are several theories on why this could be.

- Advancements in battlefield medicine are saving more veterans who in the past, would have died from their injuries

- There is more understanding and screening for Traumatic Brain Injury (or TBI)

- There is more screening and for mental health disabilities like PTSD

- Veterans are more informed about their VA benefits, and seek out help more often than previous generations

This jump in disability ratings means that more veterans are seeking treatment after leaving the service. PTSD and TBI are labeled “the two most prolific wounds coming out of these wars.”

Close to 25% of OIF and OEF veterans have been diagnosed with PTSD, and nearly 7% have been diagnosed with TBI. The average cost to treat these individuals is six or more times greater than those without these specific combat injuries.

Why PTSD Developes

The prevalence of PTSD in our OIF and OEF veterans is no surprise. According to a VA study;

“…some 95 percent of OIF combat veterans reported seeing dead bodies. 93 percent said they had been shot at, 89 percent said they had been attacked or ambushed, 86 percent received mortar or rocket fire, and 86 percent said they knew someone who had been seriously injured or killed.”

We can’t pin down why PTSD develops, usually months after being exposed to trauma, but there are some theories out there.

- A survival mechanism – your body may be forcing you to re-live these experiences in preparation for future traumatic events

- High adrenaline levels – studies have shown that veterans with PTSD have high levels of stress hormones like adrenaline. Adrenaline creates a ‘fight or flight’ sensation. Since these veterans continue to make this stress hormone even outside of dangerous situations, it may explain their feelings of hypervigilance and numbed emotions.

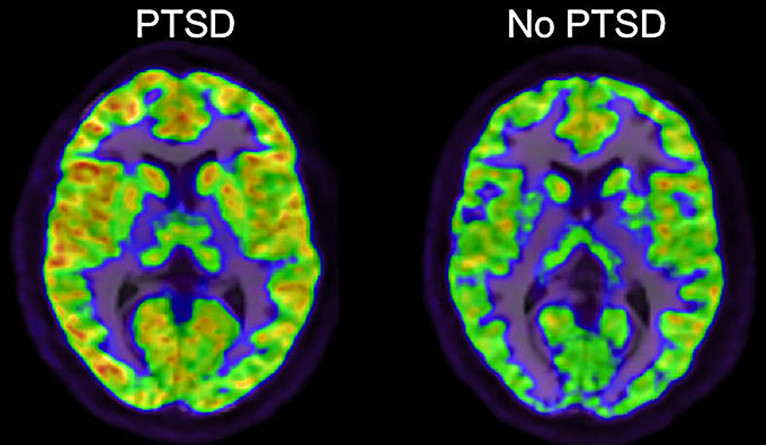

- Physiological changes in the brain – brain scans of people with PTSD differ from normal brain scans. The hippocampus (which is responsible for memory and emotion) is smaller in these scans:

Suicide and Post 9/11 Veterans

You have probably heard that suicide is a major issue for the Department of Veteran Affairs. From 2001 to 2014, vet suicides have jumped 32 percent. The problem is worse among female veterans, who saw their suicide rates rise more than 85% in the same time, in comparison to about 40% for civilian women. Even though veterans only make up roughly 9% of the US population, they accounted for about 18% off all suicides.

Data that shows us the demographics of suicidal veterans, show that post 9/11 vets have higher rates of suicide than previous generations. Even with more comprehensive help available to them, OIF and OEF veterans still struggle with suicidal ideation and other comorbidities.

The VA has set up several programs to help veterans in need. They hired a huge number of new employees, about 5,300 mental health support personnel, to try and combat the problem. There are countless non-profits who are also offering help to suicidal veterans. However, it remains a top concern. The VA has come under criticism for not funding or supporting complimentary treatment, like accredited service dog programs.

Post 9/11 veterans are a distinctive generation of warriors who face hurdles that they sometimes need help to get over. These wars have gone on for more than 15 years and many veterans have seen multiple deployments in their careers. Without a clear end in sight, these horrific suicide and mental health statistics that we see today will only climb. We need to be vigilant in finding new and effective ways to help heal out soldiers as they come home and go back to their families.